While at the Grosvenor Small and Emerging Managers Conference last week in Chicago, I started thinking about alpha. Despite all of the naysayers out there quick to announce the death of alpha, I would actually suggest that alpha is alive and well and living in many portfolios. I think maybe investors, quick to flock to a very concentrated handful of extremely large funds, have forgotten where alpha lives and what drives alpha.

For that reason, I’d like to announce the formation of a new co-ed fraternity. A fellowship, if you will, called Mi Alpha Pi. Mi Alphas have no dues and no secret handshake. We are merely called upon to remember that alpha comes in different size funds, diverse managers, life cycle investing and from innovators.

MI ALPHA PI

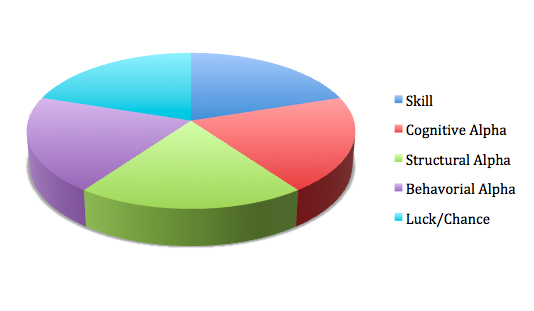

WHERE DOES ALPHA COME FROM?

Skill – Obviously, this is what we want in all of our hedge fund managers: the ability to find and make the most of investment opportunities. Skill comes from a variety of sources. Intelligence, experience, intuition, emotional awareness and other factors contribute to manager skill. Skill is long-term and must be judged in a variety of market environments, good and bad. And in Mi Alpha Pi, we don’t believe that short-term losses necessarily are indicative of loss of strategic acumen. We even have special hazing for investors that think that way.

Cognitive Alpha – Cognitive alpha comes from being able to think about the markets and investing differently than your investing peers. Instead of looking at Apple and AIG along with every other large hedge fund, these managers look outside the box. Many investors have a tendency to be heavily influenced by market news and earnings and, over time, buying attention-grabbing stocks has a tendency to diminish returns. How do you find cognitive alpha? Look to contrarians, women and minority run funds for less homogenized thinking.

Structural Alpha – There has been a plethora of research, including my own at PerTrac, that suggests smaller, emerging managers outperform larger, older funds. One of the reasons why this may occur is what I will call “structural alpha.” When a fund is small it can take advantage of niche plays and club-sized deals that larger funds may ignore. They also may have fewer issues with liquidity, volume and short-squeezes. As a result, emerging funds may be able to exploit their smaller structures to produce outsized gains.

Behavioral Alpha – Although it’s difficult to separate behavioral alpha from cognitive alpha, I think it is an important distinction. Cognition is how you think about the world, while behavior is what you do with that information. Behavioral alpha may be created by less frequent trading, less inopportune trading and infrequent return chasing. Young funds and women and minority owned funds may be fertile grounds for behavioral alpha.

Luck/Chance – It is difficult to admit that sometimes what we think is alpha is really just luck or chance at work. For example, in the late 1990’s when I first began researching hedge funds, there were a number of funds that had no real shorting skills but that, at the time at least, didn’t need those skills. The rising tide of the bull market lifted all ships, so to speak. However, when the markets broke during the tech wreck, it was quickly evident which hedge fund managers were wearing no clothes, luckily figuratively and not literally. This is why it’s always critical to ascertain whether a manager is riding a good strategy or a good market.

It’s time to look a little further than the 500 largest hedge funds to find excess returns. Finding alpha isn’t always easy, but the 2014 pledge class of Mi Alpha Pi is looking forward to welcoming you.