As we enter 2015 refreshed from vacations, overstuffed with tasty victuals and perhaps even slightly hung-over, it’s time for that oh-so-hopeful tradition of New Year’s resolutions. Many of you probably resolved to spend more time with your family, eat better, exercise more, floss daily, or to give more to charity. Despite what the research says, some of those resolutions may even stick. So before the holiday afterglow completely fades, I would like to turn attention to some investing resolutions, designed to bring more (mental) health, wealth and happiness in 2015. Without further ado, here are my top three New Year’s resolutions for investors. (Due to the length of this post, I’ll cover money manager New Year’s resolutions in next week’s blog.)

Investor Resolutions for 2015

I resolve to not confuse absolute and relative returns – When you profess to want “absolute returns” you do not get to invoke the S&P 500 in the same breath. In 2014, “absolute return” came to mean “I expect my investments to absolutely beat the S&P 500” or “My investments absolutely cannot lose money (or I will redeem them at my first opportunity).”

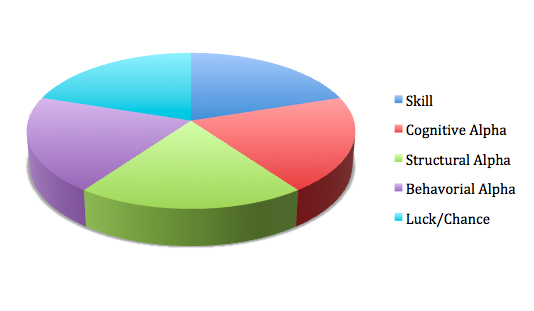

Absolute returns actually means you make an investment in an asset class or strategy and then you judge whether you are happy with those returns based on absolute standards. Did the strategy perform as expected, based on returns, volatility, drawdown, and/or diversification? Do I still believe in this strategy or asset class going forward? If there was a loss, do I believe this is a substantial, long-term problem or is this a buying opportunity? Trying to turn absolute investments into relative investments after the allocation fact causes a lot of knee-jerk investment decisions, leads to return chasing and, ultimately, underperformance.

I resolve to not get tied up in my investing underpants – This probably needs some explanation because I do not want any of my blog readers to Google “tied up in underpants” - the answers you get will absolutely not be suitable for work.

Instead this (quaint?) colloquial saying basically means that you shouldn’t get so wrapped up in perfecting the small things (underpants) that you can’t get to the big stuff (getting dressed and leaving the house). For example: “That meeting was worthless. We spent all morning tied up in our underpants about where to get lunch and we didn’t address the sales quotas.” For non-Tennesseans, the less colorful turn of phrase would involve forests, trees and all that.

When it comes to investing, there are any number of “underpants issues” with which to deal. Fees are a great example. Every time someone wants to argue with me on Twitter about alternative investments, they inevitably start with “You don’t have to pay 2%/20% to [get diversification, manage volatility, achieve those returns, etc.]."

It’s always interesting to chat with these folks about what they think an appropriate fee structure would be. Most people say they are willing to “pay for performance.” And in fact, perhaps with the exception of investments into a small number (less than 500) of “billion dollar club” funds, you are.

Since more than half of all funds have less than $100 million in AUM, it’s pretty difficult for the bulk of funds to get rich from a management fee alone. Management fees tend to be, on average, around 1.6%. In comparison, mutual funds charge between 0.2% (index funds) and 2% in management fees, with the average equity mutual fund charging, according to an October 6, 2012 New York Times article, around 1.44%. Not that different, eh? As for the incentive fee, that only gets paid if the manager makes money. It’s designed to align interests (“I make more if you make more”), not steal from the “poor” and give to the rich. Perhaps a hurdle makes sense, but why dis-incent a manager entirely?

At the end of the day, this laser focus on fees hampers good investment decision-making. We run the risk of focusing too much on what we don’t want others to have than on what we might get in return (diversification, a truly unique or niche strategy, reduced volatility, expertise, returns). We run the risk of negative selection bias (with managers and with strategies) if we choose only low fee funds. We also risk dis-incentivizing smaller, niche-y and more labor-intensive start-up funds, which could completely homogenize the investment universe.

Is there room for fee negotiation? Of course. I am a big proponent of sliding scales based on allocation size or overall AUM. However, making fees your sole decision point is, I believe, penny wise and pound foolish over time and will leave you, well, tied up in your underpants.

I resolve to take a holistic approach to my portfolio – Say this with me three times “I will not chase returns in 2015. I will not chase returns in 2015. I will not chase returns in 2015.”

Why should auld performance be forgot? Let’s look at managed futures/commodity trading advisors. It hasn’t been an easy ride for macro/futures funds. In 2012, they were the worst performing strategy according to HFR. In 2013, they were edged out of last place in HFRs report by the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, but still under performed all other hedged strategies. The last two years saw heavy redemptions, with eVestment reporting outflows from Managed Futures funds for 26 of the last 27 months.

And in 2014? Managed Futures killed it.

Early estimates from Newedge show that Managed Futures funds returned an average of 15.2% in 2014. January 2015 predictions are that Managed Futures will either win or place amongst top strategies for 2014.

It’s always tempting to dress for yesterday’s weather, but savvy investors look not just at what’s performed well, but where there are future opportunities and potential pitfalls. Even an up-trending market, maybe especially in an up-trending market, it’s important to look to out-of-favor and diversifying strategies, niche players and contrarians to create a truly “all weather” portfolio.

Stay tuned for money manager resolutions next week, and in the meantime, best wishes for a Happy Investing New Year.