Throughout my childhood I owned and rode a bike. In the 70s and 80s, no one gave two figs whether I did so wearing a helmet or not. Seriously, we drank out of the garden hose and trick or treated at houses where we didn’t know people, too. Those were wild and crazy years.

In the 1990’s, however, someone decreed that biking was entirely too dangerous to be attempted without a helmet. I promptly stopped biking. For those of you that have met me, or who have even seen my picture, you probably recall one critical fact about my appearance: I have Big Hair Syndrome.’ And it ain’t fitting under a bike helmet.

Flash forward 20 years and we’re discovering some interesting facts about the bicycle helmet craze. In places where bicycle helmets were required by law, bike trips decreased by 30-40% across all demographic groups and by 80% across secondary school aged girls.

Unfortunately, when people gave up their bikes, they also gave up the health benefits of riding. One study by the Brits suggested that the health benefits (in terms of increased longevity) of riding outweighed the risk of injury by 20:1. A study done in Barcelona put this figure at 77:1. In Australia, they found 16,000 premature deaths caused by lack of physical activity dwarfed the roughly 40 cycling fatalities that occurred each year.

And that’s the curious thing about risk. You can focus on a single risk (in the case of biking, that a head-on collision will occur at 12.5 mph) to the exclusion of all else and actually increase your risk of other types of injury.

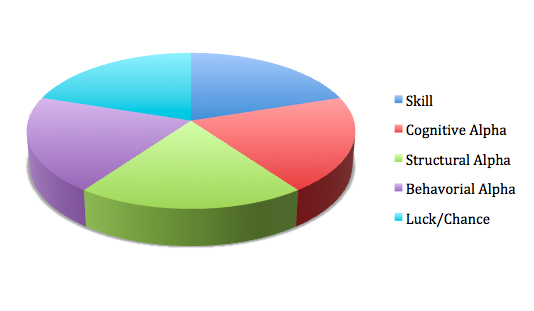

This is especially true in investments, where there is no single definition of risk. There are a multitude of risks against which to guard, and most of them have corresponding risks they introduce. For example, if you maximize the risk of illiquidity (the risk that you can’t get to your money when you need it) you may compromise returns. Private equity has been the best performing strategy over the last 10 years, but locks up capital for 5-10 years depending on the fund. Likewise, venture capital, which has been on fire for the last few years, has a 10 plus year lock up. Requiring high liquidity restricts the types of investments you can make, which can impede diversification. More liquid investment structures can have lower returns than less liquid investments because they allow for people to trade at exactly the wrong times. Don’t you know someone who sold his or her mutual funds or index funds at the exact bottom of the market? In addition, there can also be a lower premium on more liquid instruments.

Or consider headline risk. Remember the Chicago Art Institute and Integral Capital? When Integral blew up and the Art Institute was a large, and the only, institutional investor in the fund, the headlines abounded. Since that time, there’s been an acknowledged risk of being in the headlines for losing money. For this reason, many investors stick to the same small group of funds so that they’re not alone should the ‘fit hit the shan.’ Unfortunately, this leaves a lot of smaller, less-well-known managers in the cold, and can compromise returns as well. It also increases concentration in a small number of managers, funds and strategies.

And what about fee risks? Being ‘penny wise and pound foolish’ can block access to some of the most successful (read: non-negotiable) managers and funds. It can also cause investors to eschew entire asset classes (private equity, hedge funds) increasing correlations and concentrations and reducing diversification. Or what about the risk of not beating a benchmark like the S&P 500? Chasing returns is not very productive in the long run, and it can cause investors to take unnecessary risks in order to beat a rising benchmark. It’s also difficult to outperform on both the up- and down-side, so targeting outsize bull market returns can lead to bear market catastrophes.

In short, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Protect yourself single-mindedly from one risk, and you just increase your odds of obtaining a different type of injury.